Structuring for Impact

Written by: Annika Voltan, Executive Director, CSCNS & Sandra McKenzie, Co-founder, Forge Institute

This article is the fourth installment in a series focused on stimulating discussions and ideas for a healthy Community Impact Sector transformation and recovery in Nova Scotia!

In our introductory article “We Need a Healthy Community Impact Sector – Here’s Why You Should Care” we took a big picture view and made the case for why a vibrant sector should matter to us all. The second was called “Overworked and Undervalued: Sustaining the Community Impact Workforce” and focused on workforce strengths and challenges as part of the call for fresh ideas and models to ensure sector sustainability and vibrancy. We followed up with “Unraveling an Unsustainable Funding Model“, where we applied a lens to the complex funding environment that nonprofits operate within. In this article we are reflecting on current governance models and imagining new ways to structure for greater impact.

So, what is “governance” and why does it matter?

One of the challenges we faced when framing this article was working through what is included in the term “governance.” Developing a common understanding of what it means and establishing what an effective model looks like is central to sector transformation. The concept includes accountability and decision-making through defined roles and responsibilities, as well as administrative functions related to operations, staffing, volunteers, relationships with partners, funders and more. The concept is complex. Current models are outdated and need a redesign.

“Governance determines who has a voice in making decisions, how decisions are made and who is accountable“.[1]

Typically, when we mention governance in the context of nonprofits we think of the Boards of Directors. Beginning in 2018, the Ontario Nonprofit Network (ONN) partnered with Ignite NPS to reimagine governance for the nonprofit sector in Ontario. They discovered that:

“Many people are confused about what is meant by ‘governance’ in nonprofit organizations. For instance, some interpretations are based on an assumption that ‘governance’ and ‘the board’ are interchangeable, even though organizational governance is part of a larger, complex system, and the board is just one of the structures put in place to implement it. Its interpretation can also reflect very different ideas about power, accountability, and authority.”

Leading in a Complex World

Boards are certainly an important part of governance, but organizational leaders are held accountable by multiple stakeholders with often competing needs

- Funders have financial and reporting requirements affecting programming.

- Clients and community members have needs that may differ from funder priorities.

- Board members have a fiduciary duty to ensure the organization’s mission is pursued and financial controls are in place.

- Staff have personal values and motivations attracting them to the work, and roles and responsibilities to make it happen.

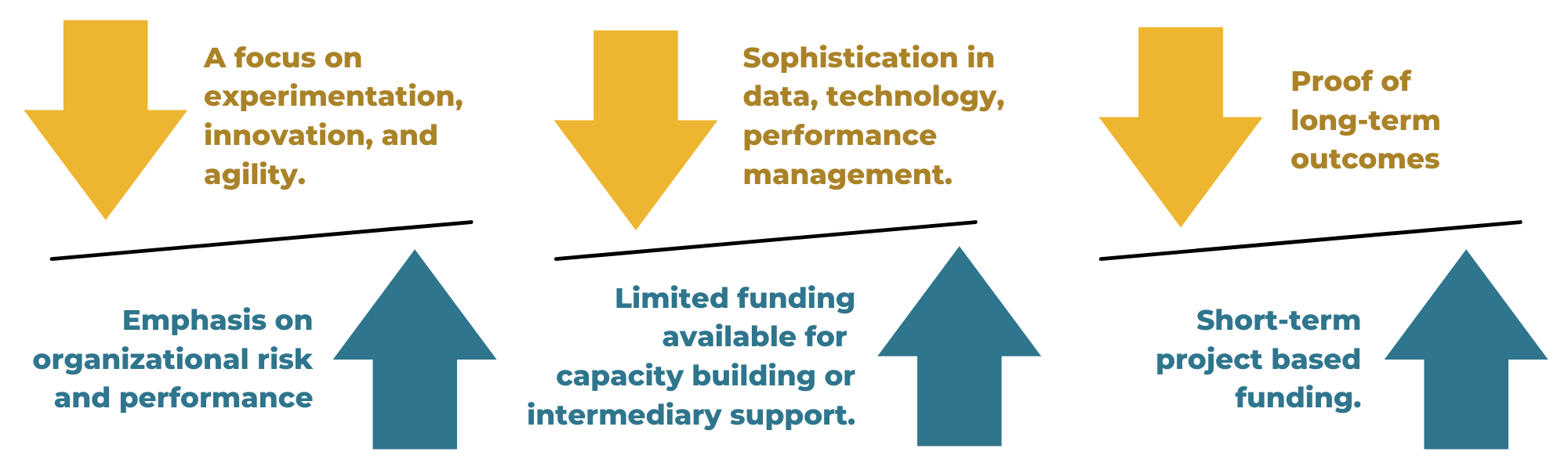

The push and pull of trying to be innovative, data-driven, and evidence-based in an environment shaped by short-term project funding leads to a variety of organizational tensions, as shown in the below visual adapted from the ONN report:

Executive Directors often find themselves in the seemingly impossible role of balancing these tensions and stakeholder needs. In small organizations (64% of nonprofits in NS have fewer than 10 staff), leaders oversee the vast majority of operational functions, from financial management to HR management to communications, and everything in between. The result is that many sector leaders spend the majority of their time managing funders, board needs, and operations – versus focusing on the organization’s mission and impact.

If we consider that there are more than 6,000 registered nonprofits in Nova Scotia and each of those is required to have a Board of Directors (comprised primarily by volunteers), it doesn’t take long to recognize the absurdity of the existing model and the demand it places on staff and board members. The same can be said for the expectation that each of these small organizations has the capacity and skills to manage all aspects of operations effectively and strategically.

In addition to these challenges, a number of significant societal shifts are underway that are driving the case for change in the Community Impact Sector:

- Fewer Volunteers: The number of volunteers and expectations related to volunteering are shifting. Through COVID-19, many organizations reported reductions in volunteerism. Through an engagement process with young leaders, ONN found that many emerging leaders perceive governance work as “demanding, with onerous and complex accountability in an environment of underfunding and restricted capacity to innovate”.

These challenges will be amplified by impending retirements amongst nonprofit leaders across the province, and felt acutely in rural communities.

This is cause for significant concern when considered with the findings of the APEC Report on the State of the Sector in Nova Scotia which pointed out that, “Volunteers are critical to the success of many nonprofit organizations. A drop in volunteer hours between 2007 and 2013 is equivalent to the loss of 1,500 full-time jobs. If this trend continues nonprofits will have to rely more on paid staff, automate or reduce their services. Encouraging volunteerism, especially for younger workers and new immigrants should be accelerated.”[5]

- Need for Diverse Voices to Inform Decision Making: The challenge of dwindling volunteers, to both support operations and guide organizations, is compounded by the need for a diversity of voices to inform decision-making. Current governance models rely on diversifying boards to achieve this goal, but unless board structures and practices shift fundamentally, challenges will persist with attracting and retaining members from equity-deserving groups. New ways of thinking about governance can include shared-decision-making mechanisms which increase diversity, involve more voices, and capitalize on a wider range of competencies than a handful of board members can provide.

- Need to Partner Across Organizations: The need for innovative approaches to fulfill governance comes at a time when there is more pressure and more opportunity for nonprofit leaders to adopt a shared leadership model with staff, in their governance work and at collaborative tables. A Mowat NFP paper, Peering into the Future, says, “There is a growing literature that suggests that new, transformative and adaptive approaches to governance are needed to ensure better responsiveness to social issues, system-wide impact and adaptability to the changing environment. This thinking envisions governance as more collaborative – a function that can be shared and not limited to the board.”

Collectively, these drivers point to the need for transformed governance models. There must be a better way!

Structuring for Impact

The case for governance transformation begins with its foundation. In many ways, nonprofits have adopted a corporate governance structure with little adaptation, resulting in norms and processes better suited to company boardrooms than grassroots organizations. But the missions of businesses and nonprofits are fundamentally different, “The nonprofit board has to make decisions that balance mission with the bottom line. Corporate boards don’t have those trade-offs-there is no mission beyond making money.”[9]

In his provocative and popular blog, Vu Le comments on the archaic and toxic nature of nonprofit boards. He refers to them as, “A structure where groups of volunteers who barely know one another, see one percent of the work, often don’t reflect the communities we serve, and who may have little to no experience running nonprofits, being given vast power to supervise leadership and determine values, policies, and practices”. He calls for a reimagination of existing structures, where power is shared more evenly between the board and staff and the role of the board is reexamined. Another recent article published in the Stanford Social Innovation Review on decolonizing governance notes the unavoidable power dynamic between the board and staff, but advocates for examining how that dynamic plays out so that it doesn’t replicate or perpetuate harmful, discriminatory behaviours.

In an Ontario study that engaged emerging leaders around the topic of next generation governance, a series of system-level and organization-level recommendations were put forward to help ensure young people continue to engage in the sector. Themes surfaced in relation to the need to develop healthy workplace cultures, agile and participatory decision-making models, and a focus on impact over sustaining organizational structures.

The need for a new governance model for nonprofits was echoed by ONN’s Reimagine Governance research and engagement process, which found that the key issue needing to be solved is, “That governance of nonprofit organizations isn’t well designed to be consistently effective and able to respond to today’s complex environment, nor the future. This includes the form governance structures take, the way governance functions are fulfilled, and how they all work within its ecosystem.”[13]

Exploring new models for decision-making at all levels is foundational to transformation in the Community Impact Sector.

What if we designed nonprofit governance to work effectively in a complex environment, align with the needs of the sector, include more diverse voices and be flexible enough to support partnerships across organizations?

We have the will, let’s find the way.

We want to hear from you!

Please consider taking a few minutes to share your ideas on key challenges to address for sector transformation and recovery!

Click Here[1] September, 2018. Peering into the Future – Reimagining Governance in the Non-Profit Sector (p.4). Lisa Lalande. Ignite NPS. Mowatt Research #171. https://theonn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Mowat-Peering-into-the-Future.pdf

[2] September, 2019. Reimaging Governance – Framing Forward Document. Ontario Non-Profit Network and Ignite NPS. https://theonn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Framing_summary_Reimagining_Governance_Final_Oct_2019.pdf

[3] Ibid. Pg.13.

[4] August 3, 2018. “Accountability: for what, to whom and how – the role of the Board”. Governance Today (Blog Post) https://www.governancetoday.com/GT/Latest_News/News_Articles/GT/News_Articles.aspx

[5] April 2020. The Atlantic Provinces Economic Council’s Report The State of the Nonprofit Sector in Nova Scotia. https://www.apec-econ.ca/research/?site.page.id=50004&do-search=1

[6] September, 2019. Shared Decision-making for Nonprofit Governance. Ignite NPS. https://theonn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/SharedGovernance_final-Sep2019_v2-002.pdf

[7] Shared Decision-making for Nonprofit Governance. Pg.4.

[8] Wells, P. (2012). “The Non-profit Sector and its Challenges for Governance”. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics vol. 9(2) p.84. Accessed at: http://www.na-businesspress.com/JLAE/WellsP_Web9_2_.pdf

[9] Trustee Magazine (2005). “Who Does It Better? The Corporate versus the Nonprofit Governance Model” American Health Association. Accessed at: https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/u.osu.edu/dist/d/47198/files/2010/01/For-profit-vs-nonprofit.pdf

[10] https://nonprofitaf.com/2020/07/the-default-nonprofit-board-model-is-archaic-and-toxic-lets-try-some-new-models/

[11] Walrond, N. (2021). Decolonize Your Board. Stanford Social Innovation Review.

[12] Barakzai, A., Lai, A. & Mollenhauer, L. (2018). Next Generation Governance: Emerging Leaders’ Perspectives on Governance in the Nonprofit Sector. Accessed at: https://pillarnonprofit.ca/news/next-generation-governance-emerging-leaders-perspectives-governance-nonprofit-sector.

[13] ONN (2019). “Framing Forward: Reimaging Governance”, p.7. Accessed at: https://theonn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Framing_summary_Reimagining_Governance_Final_Oct_2019.pdf

Wonder if you’ve looked at cooperative models?

Coops are guided by seven principles that are relevant to some of the concerns you raise.

Open and Voluntary Membership. (diverse voices)

Democratic Member Control. (diverse voices)

Members’ Economic Participation. (some of the volunteer issues)

Autonomy and Independence. (funder interference)

Education, Training, and Information.

Cooperation Among Cooperatives. (partnering across organizations)

Concern for Community.

This is a very interesting paper. As a past volunteer in CSC, C@P, and several other small community organizations, I can see the need for consolidation efforts. As I see it, the challenge is attracting small community groups, without destroying their individuality. This will be an opportunity of monumental proportion, but with huge benefits for all involved. I would certainly be interested in being part of this enterprise.