Diane Connors

Communications Director

Lydia Phillip

Content Strategist

This piece is greeting the world in proximity to the Day for Truth and Reconciliation in what we now know as Canada. We acknowledge our connection to decolonizing practices and our teachers – Diane Connors from an activist lineage, supporting grassroots Indigenous leaders in the climate change space; Lydia Phillip from her anti-racism and equity work supported through anti-colonial practices and principles of Black Liberation.

What does it mean for us when the leaves start to change colours, the mornings now have a dewy chill, and the light slants differently? When the gardens and plants slow their growth and offer seeds, when the children return to school, and we start to spend more time indoors? What does it mean for us when we return together as a team after time away by the water and in summer sun?

IONS, like many organizations, is preparing for a year of activity after taking time this summer to rest, plan, and readjust. We have spent time welcoming new staff, developing our team structures, strengthening self-leadership, implementing supportive practices, and adjusting policies and procedures to honour our staff’s actualization as people. We were able to hold a significant amount of space to debrief our winter and spring work, and to develop an evolved organizational strategy.

And throughout these processes, we have recognized the importance of spaciousness and forming new mentalities around time in a productivity-driven society. Below we explore the idea of time as it relates to our work – in particular, the decolonizing and anti-capitalist practices that can support more just and equitable organizations.

The Extractive Nature of Colonialism

We continue to weather the consequences of colonialization – social injustices, a climate crisis, and environmental disasters. We deplete the oceans of resources, deforest our lands, and bulldoze communities. The capitalist focus on quick production ignores the natural cycles of water and earth, trading sustainability and healthy ecosystems for short-term gain. We take, pull, mine until there’s nothing left. This is true for our bodies as well. Capitalism encourages us to see time as a commodity that can be extracted from people, leaving little space for regeneration. Our humanity is disregarded with our time viewed as means for production.

Our relationship with time has been largely shaped by colonialism, soliciting respect only if its production is deemed profitable under capitalism. Indigenous and non-colonial ways of being with time have been disparaged, oppressed, and demeaned. Larissa Crawford, Founder of Future Ancestors, discusses how British colonization, which was embedded in industrial-capitalist, Christian ideologies used time structures to dehumanize, other, and insert superiority over Indigenous communities. The surveillance and control of time is a white supremacist practice, leading to the enslavement of Black and Indigenous people, the exploitation of racialized communities, and harmful “shortcuts” in the name of profit.

A huge source of harm has been a relationship to time that centers productivity with a capitalistic understanding of what it means to be valuable, what it means to be productive, and that shapes our understanding and relationship to self, to money, to work, to land, and to rest. – Larissa Crawford, Future Ancestors

The unrelenting pace we need to sustain in order to produce value is one of the many remnants of a colonial legacy. It’s not feasible nor sustainable to expect our bodies and minds to maintain the same level of energy throughout the year. The Mi’kmaw concept “Netukulimk” speaks to caring and stewarding the land, reciprocity and respect between beings and the environment, and the responsibility of maintaining balance. Re-examining our transactional relationship with time – acknowledging how productivity and urgency culture have historically been used to uphold white supremacy – is a decolonizing practice. How can we think and act differently in relation to time and seasonality to enable people to be well, to be human, and to do their best work?

Honouring peoples’ existence outside of their labour, and respecting the time and energy required to do just and equitable work is an anti-colonial approach. It’s redefining our value, allowing us to slow down – not as a reward for exhaustion, but because of our inherent worth and humanity.

Time and Space as a Practice

The practice of slowing down is widely recognized as necessary in the Community Impact Sector, but far harder to implement. New opportunities arise and need to be actioned immediately for fear of missing out. We feel compelled to take on too much with not enough time or resources. We overload ourselves and strain the good-hearted people we work with, and we push through year after year. There’s a feeling that we must work this way, because those we serve don’t have the luxury of time.

Our team has been practicing different ways of being with time to combat urgency culture and to organize our work in a way that encourages natural flow and rhythm. Building toward a “culture of care” has not been easy, fast, or mess-free. Changing how we work has required a lot from our team – mental fortitude, self-leadership and honesty with ourselves, brave communication, and the ability to identify patterns and traps that we perpetuate as a group. Unsurprisingly, it has required time – time to think, to feel, to practice, and to try again.

Re-evaluating our time and prioritizing people looks like manageable workloads, adjusting expectations, radical generosity, saying “no”, respecting boundaries, and creating access to rest. Below are some specific examples of how IONS is trying to respect time and seasonality in our work.

Internal Operating Rhythm

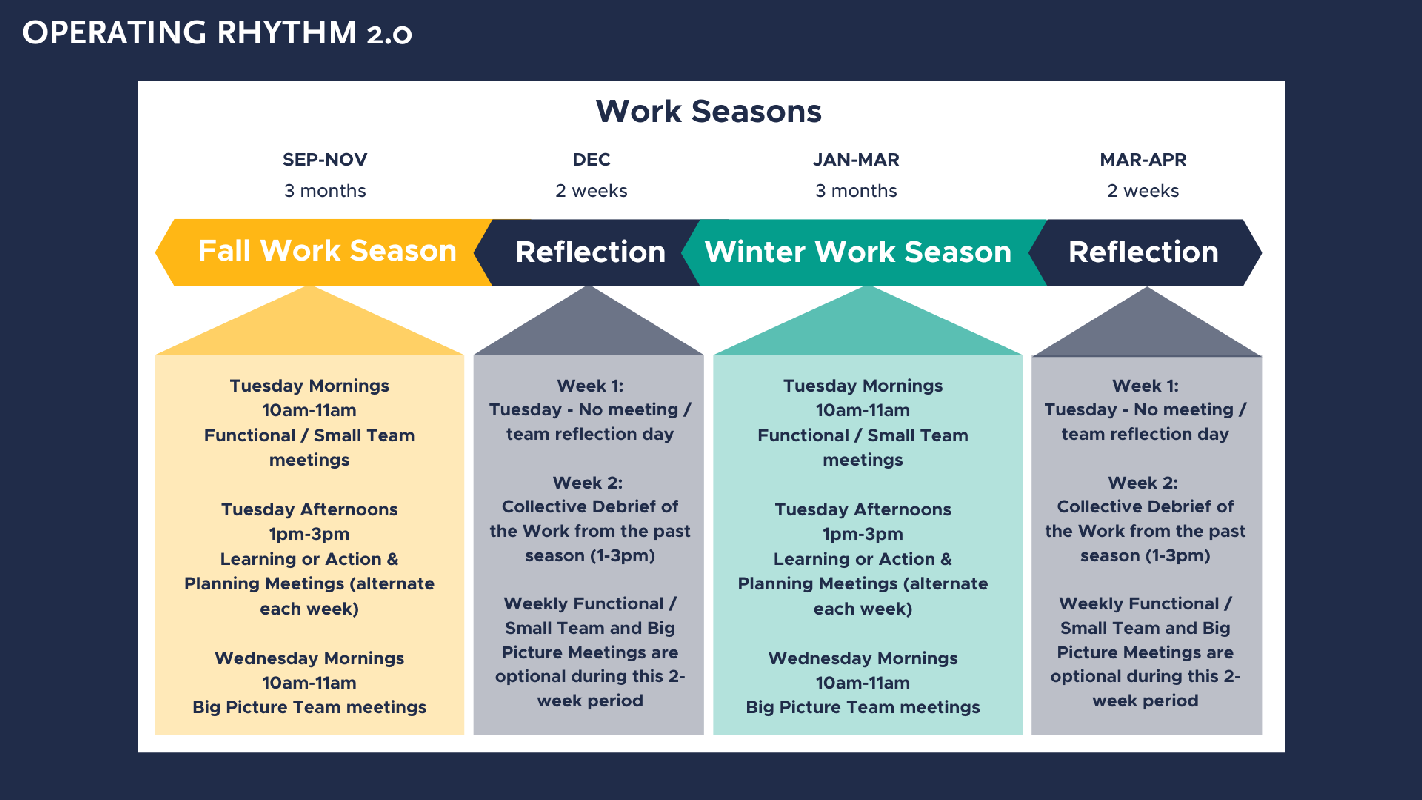

IONS often has heavier periods of activity in the fall and spring, and we’re experimenting with a new annual cycle based on the seasonality of our work. This “Operating Rhythm” recognizes three-month cycles of activity and builds in two weeks of spaciousness to reflect, plan, and rest afterwards. During this protected time our goal is to regenerate, minimize internal meetings, pause external work, and collectively debrief. In addition to an annual operating rhythm, we also have shorter cycles. Our team agreed on a structure of weekly gatherings that flow into one another at different levels – including 1-on-1s with supervisors, departmental team meetings, and time together with the full team. These cycles allow us to be intentional with our time, flow information across teams, and feel supported.

Organizing our time in this way helps to combat harmful characteristics of white supremacy culture such as urgency, quantity over quality, and production at the expense of ourselves and each other. Predictability can also help our team feel more settled and prepared. It helps us to manage our workload, prioritize relationships, and be in community. The hope is not to be overly prescriptive with our time, but to honour the speed of building trust, and to formally acknowledge cycles of rest in our work.

Flexibility and Time Off

Vacation leave starts at four weeks at IONS, and the office closes over the winter holiday season to give staff additional paid time off to rest. IONS also has a generous wellness policy that includes time off for physical ailments, mental health, and menstruation. We support hybrid and remote work to be inclusive of different lifestyles, locations, and abilities – and a newly approved policy gives staff an annual budget for home office supplies. Our team understands that there are different ways of working, varying familial obligations, and increasing cost of living expenses, and provides flexibility and trust around individual schedules.

IONS’ experimentation and implementation of a permanent four-day work week was more than just working four days. The justice and equity considerations included mental health aspects, abilities, differing parental and household responsibilities, rest, and pushing back on colonial, capitalist ideologies of our worth. We do not work on Fridays in order to slow down, reconnect with ourselves and others, and to recharge with the things that bring us joy. With capitalist notions of time and value tied to working hours, it was important to demonstrate people’s value holistically. Staff are not expected to “pick up” the extra hours Monday through Thursday and everyone’s salary stayed the same despite working less.

A human-centered lens to policy and practices can help rebalance traditional, inequitable exchanges of labour and create healthier, more sustainable workplaces.

Realistic Workloads and Timelines

In recognition of individual gifts, we know that contribution and time looks different for each person – and can fluctuate throughout the season or year. Expecting every team member to have the same work pace, stamina, and capacity is harmful and reinforces capitalist notions of productivity, ableism, and worth. When we push back on faux urgency in the day-to-day, it gives us time to build trust, understand accessibility needs and foster reciprocity within our work. Realistic workloads look like workplans that are individually tailored to be manageable and considerate. Not only does this support people who are chronically ill or have chronic pain, disabled, neurodiverse, or struggling with mental health – but it is accommodating to everyone.

Additionally, things often take more time than we allocate. Relationships, listening, processing, and learning are an imperative part of the work that takes space and energy. Realistic timelines require a recalibration of our collective conceptions of time, urgency, and productivity – and how we prioritize. This can mean co-creating and adjusting deadlines, saying “no” or “not right now” to external pressures to produce, allowing time to process, and building spaciousness into work seasons. Part of decolonizing our relationship with time is valuing the time spent on items that are often deemed “unproductive” by a capitalist definition.

The Responsibility of Leadership

An important part of being able to implement new ways of working with time and seasonality is the role of leaders. Though in a strong organization each person holds different kinds of power, it’s important to recognize the positional power of those with formal leadership. Leaders often set the pace – they hold ultimate decision-making power over deadlines and deliverables, and are the most common vector for new work entering an organization. A leader can help manage the workload and protect the time of their people, or they can overload the team and maintain the status quo.

It’s a difficult job for leaders – especially Executive Directors – who feel the pressure of addressing so many needs without enough time or resources. But we also know that burnout, conflict, resentment and turnover fragments and halts the work. And when leaders burn out as a result, the work doesn’t get done in the end regardless.

At IONS, it has been a process of practice and reflection to develop leadership structures that uplift the skills and mentalities that bolster a strong team. Encouraging leadership practices that are in alignment with principles of justice and equity are helping us develop a culture of care.

Just and Equitable Workplaces

This attention to time, space, and people has been part of an imperfect practice of what we have called “JEDDI” work (justice, equity, decolonization, diversity, and inclusion) for the past few years.

Like most beings, organizations often go through stages – cycles of budding, dormancy, and sprouting anew. But the ever-present question has been, “What does it actually mean to embody “JEDDI” in our work?”. And with such a complex multi-dimensional and intersectional concept, we have revisited how we can talk about JEDDI in a more accessible and authentic way. Though the work hasn’t changed, simplifying language can be more approachable. And, given the timing of our new strategic plan, we can communicate this shift in our theory of change moving forward.

In our next phase, we’ll call this body of work “justice and equity” as we continue to challenge our assumptions and shift accordingly toward decolonizing and anti-colonial practices. We can live these values by rejecting capitalist, white supremacist norms in commitment to more just, equitable workplaces, community spaces, and being.

“I know this seems impossible for many people working within the rigid structure of capitalism. But changing your relationship to time is possible no matter where you work.”

It’s been gratifying to see the shifts as we nourish a kinder, more supportive relationship with time and seasonality. Releasing a new organizational strategy has been a good opportunity to reflect on our conceptions. The process of developing this strategy has been almost a year in the making. It’s been less about making the perfect plan, and more about the space to think through our purpose and intentions, to align with one another, and to be considerate about how we are shaping the work we do. Our hope is that in being thoughtful and taking the time needed, our work flows with less urgency and more autonomy.

So, what does it mean when the days grow shorter and the nights colder, the branches shrug away their leaves, frost forms intricately on our windowpanes, and we are together in our sweaters sharing warm food? For us it means that it’s time to connect, generate energy with our ideas, and harvest the seeds that grew from the summer season.

Diane Connors

Communications Director

Diane supports communications and engagement work at IONS. She helps implement processes, project plan, and facilitates collaboration across the team so that our work reflects the collective intelligence of our people and communities.

Lydia Phillip

Content Strategist

Lydia stewards IONS’ external communications, branding, social media, and website development. She creates content and contributes to IONS’ work through championing the sector through her power in writing and storytelling.

Liked this post? Please share!

Thank you for your continuing thought (and) leadership — the ideas and the actions/non-action that make it easier to understand that rest and resistance are connected, possible and, indeed, necessary.